The 3rd PARI-ERI Joint Workshop Detailed Report

Oct. 31, 2014

The 3rd PARI-ERI Joint Workshop Flash Report

日本語ページへ

ASEAN Connectivity: Power Integration between Thailand and Myanmar

| [Date] | Thursday, October 2, 2014, 10:30-16:30 |

|---|---|

| [Venue] | Energy Research Institute (ERI), Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok |

| [Co-hosted by] | Energy Research Institute (ERI), Chulalongkorn University Policy Alternatives Research Institute (PARI), the University of Tokyo |

| [Supported by] | Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) |

Morning Session

Where we stand: Improving electricity access in Myanmar

Welcome Speech

Ms. Dawan Wiwattanadate, Vice Director, ERI, Chulalongkorn University

Opening Speech: Scope of the ERIA/UT Research

Prof. Ichiro Sakata, Director, PARI / Professor, Graduate School of Engineering, the University of Tokyo Handout

Presentations

Mr. Masayuki Seino, PARI, the University of Tokyo Handout

Mr. Hajime Sasaki, Project Researcher, PARI, the University of Tokyo Handout

Q&A

Moderator

Prof. Hisashi Yoshikawa, Project Professor, PARI / Graduate School of Public Policy (GraSPP), the University of Tokyo

Afternoon Session

Way forward: Scope of work for 2014

—Power Integration with Myanmar, Thailand and China

Opening Speech: Scope of Session

Dr. Prasert Reubroycharoen, Assistant Professor, ERI, Chulalongkorn University Handout

(1) Lessons Learnt

Presentations

Mr. Shin Nakayama, EGCO Handout

Mr. Patipat Korbsook, EGATi Handout

Mr. Nobuo Hashimoto, Visiting Researcher, PARI, the University of Tokyo Handout

Q&A

Moderator

Prof. Hisashi Yoshikawa

(2) Work Plan for the next year: Scope and design of work for 2014

Study plan for the next year

Mr. Kensuke Yamaguchi, Visiting Researcher, ERI, Chulalongkorn University Handout

Q&A, Final Discussion, Closing Remarks

Moderator

Prof. Hisashi Yoshikawa

MC

Ms. Takako Sato, Project Academic Support Specialist, the University of Tokyo

Focus on Rural Electrification in Myanmar

Since the transfer in Myanmar in 2011 of political power to civilian rule, the expectation that Myanmar will become “Asia’s final frontier” has been heightened in the international community. One of the problems Myanmar faces is a paradox, wherein there is an abundance of resources but insufficient access to energy. It is common knowledge that Myanmar is a nation rich in resources, such as natural gas; in spite of this, the electrification rate of this nation, according to the Ministry of Electric Power (MOEP) of Myanmar, has not yet reached 30%. Similarly, the Energy Development Index of the International Energy Agency (IEA) rates Myanmar practically at the bottom worldwide—almost at the same level as Sub-Saharan Africa1 . An issue that complicates the problem even more is the “inconvenient truth” that access to energy is a great problem that exists in peripheral regions inhabited by multiple ethnic groups. Promoting national unity by raising the economic baseline—principally by improving the electrification rate—seems to have taken increasingly important significance, especially with Myanmar’s general election and the ASEAN economic integration both occurring in 2015.

Since 2013, the Policy Alternatives Research Institute (PARI) at the University of Tokyo has been conducting joint research sponsored by the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) on Myanmar’s rural electrification strategy. Furthermore, a study of the energy connectivity between Myanmar and Thailand has been conducted jointly by the Energy Research Institute (ERI) of Chulalongkorn University as part of the research, since October of that year. The Third ERI-PARI Joint Workshop was conducted at ERI in Bangkok, on October 2, 2014; more than 20 people attended, including Thai businessmen and researchers, with the purpose of presenting research results and conducting relevant reviews and analyses. In the morning session, the results of a quantitative study performed at PARI were presented. Those study results pertained to 1) electric power demand projection and 2) electrification cost estimations; the intention behind there was to facilitate calculations of the electrification costs of the off-grid area. In the afternoon session, the results of a study of the barriers imposed on the Thai cross-border independent power producers (IPP) in Myanmar2 as well as how they can be removed, were presented.

Morning session: Cost of electrification for regions not connected to the power grid

The morning session featured a presentation of the results garnered thus far through a study conducted by PARI. A welcome speech was given by Associate Professor Dawan Wiwattanadate (Deputy Director of ERI), followed by an outline by Professor Ichiro Sakata (Director of PARI) of a PARI study relating to an electrification strategy for the rural areas of Myanmar. The current rate of electrification rate in Myanmar is extremely low (i.e., only about 25%), according to the MOEP. This stands in stark contrast with Lao PDR, which has achieved an electrification rate of 80%—despite it too being an ASEAN nation with a late start in development. To proceed with improving the electrification rate in Myanmar—where the population is scattered across a large land area—relying on extensions of the main national grid will not necessarily prove to be highly effective. Therefore, for the purpose of our study, the national land was divided into individual zones, consisting of 1) “on (or near) grid” areas that can rely on the main grid to extend the electricity supply to them, 2) “off-grid” areas where the main grid cannot be relied upon, for practical reasons, and 3) “border” areas that can rely on neighboring capitals—such as those in Thailand or China—to electrify them individually. In particular, the quantitative study by PARI undertook trial calculations of demand projection and electrification costs for the “2) off-grid areas” where the main grid, for practical reasons, cannot be relied upon. In addition, our energy policy workshop in Myanmar, which has been conducted as part of an outreach program in collaboration with the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and the Overseas Human Resources and Industry Development Association (HIDA), was also introduced3 . The research results garnered thus far are being disseminated through networks nurtured through the policy workshop. It is expected the results will reach the domestic population of Myanmar and its government.

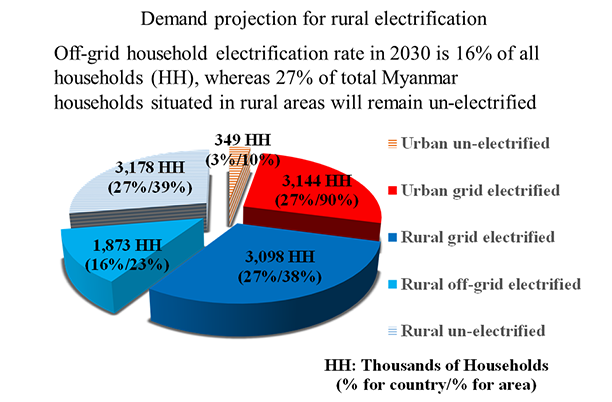

Subsequently, Mr. Masayuki Seino of PARI presented the results of the “Assumptions Regarding Demand for the Electrification of Rural Communities in Myanmar” survey. He emphasized that the study should eventually be consistent with the on-going National Electricity Master Plan study—intended for use in the formulation of a medium to long-term plan for developing the electric power sector, with 2030 set as the target year—, which is supported by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). The presentation introduced a method for calculating the number of households characterized by “off-grid electrification” (i.e., electrification without dependency on the trunk power grid), where the target electrification rate in 2030 is set to be 70%; the assumption of lower demand is from among those given in the plan proposed by JICA. Based on a rough estimate of the number of households eligible for electrification, potentially 434 MW of power would need to be generated off-grid to electrify 16% of all households that are off the power grid4 , according to Mr. Seino. On the other hand, there is the implication that 40% of the households in rural communities may be left behind as unelectrified communities (see figure 1). Such trial calculations are forced to use estimates with respect to a number of factors, such as population; for this reason, the need to make further progress has been emphasized.

Figure 1. Breakdown of numbers of Myanmar households to be electrified

(excerpted from the handout of Mr. Seino)

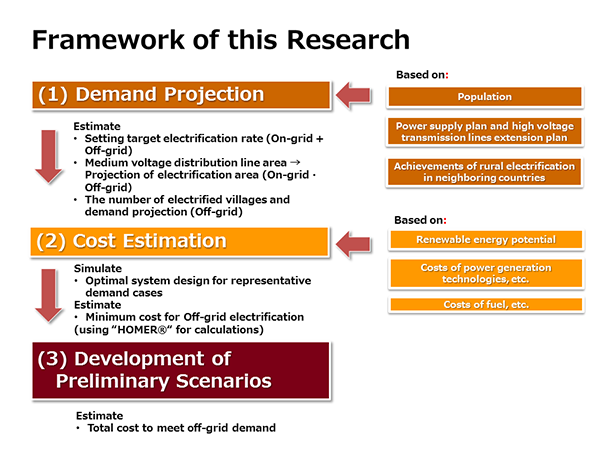

The aforementioned presentation having been made, Mr. Sasaki, a Project Researcher at PARI, gave a presentation of the results of a trial calculation of the costs associated with electrification with 434 MW of off-grid power (see figure 2 for the framework of the research). Specifically, the rural communities that would need off-grid electrification were categorized into one of six cases that involve three types of electric power demand level and two types of environmental conditions5 . Multiple combinations of solar power generation, diesel power generation, biogas power generation, batteries, converters, and hydroelectric power generation were considered; a combination of systems that could be delivered for the lowest cost was calculated for each case. These costs were multiplied by the number of rural communities that correspond to the individual cases, and summed to calculate the micro-grid cost required to electrify these communities off the power grid. As a result, the budget needed by the year 2030, if off-grid electrification were to be implemented by relying on the micro-grid, was calculated to be approximately $7.6 billion6 . The intention here was to calculate rough estimates; calculations more in line with actual conditions should be performed by conducting detailed analyses in the future.

Figure 2. Framework of this Research

Once both parties completed their presentations, an active question-and-answer session was conducted, presided by Project Professor Yoshikawa (PARI). First, there was a question regarding why wind power was not being considered as a micro-grid power-generation component. Mr. Sasaki explained that in order to utilize wind power generation in Myanmar, some issues needed to be resolved, such as the problem of low-frequency noise. Other than such issues, he also added that it was difficult to consider its feasibility, given the shortage of data regarding wind power potentials. An attempt will be made in the future to collect further primary data on site, including that relating to wind power. There was another question, regarding the potential applicability of “HOMER” software—which is used in cost estimation—in other regions. The significance of the universality of this methodology vis--vis the research was once again confirmed, by verifying its potential application in other regions. Finally, a question was posed regarding the positioning of the research; it regarded the implications sought from this project, based on costs that have already been calculated (albeit tentative figures). Mr. Hashimoto of PARI confirmed that the purpose of the analyses was simply to quantitatively evaluate, from an economic perspective, the degree of difficulty associated with implementing electrification while relying solely on independent electric power sources. Figures derived from tentative calculations will need to be replaced in the future as the reliability of research increases through the acquisition of more primary data. It will be necessary to seriously consider the significance of the calculations, which will increase in reliability as analysis results become available on the current electrification proposal of the government of Myanmar and the World Bank/Asian Development Bank; this will occur when policy recommendations are drafted.

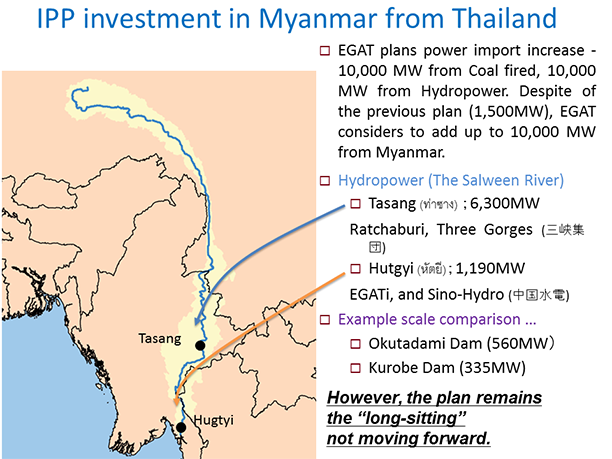

Afternoon session: Barriers to power intergration between Thailand and Myanmar, and their removal

PARI and ERI have been considering means of removing barriers to electric power integration between Thailand and Myanmar, in relation with the electrification of the aforementioned “border” areas7 . The afternoon session involved the presentation of results from joint studies, and discussions were conducted on the orientation of studies that will be implemented in the future. Assistant Professor Prasert Reubroycharoen indicated, based on the results of a joint study of fiscal 2013, that barriers are characterized by their reliance on fuel types. Dams built to generate power for export to Thailand are all located mid- and downstream of the Salween River (see figure 3)8 . Their scales are mostly 1,000 MW and over; these are extremely large, even in comparison to Japan’s Okutadami Dam (560 MW) and Kurobe Dam (335 MW). Increasing the profit margin by selling electric power on a large-scale basis makes it possible to recover the initial, earlier costs of dam construction. Still, making the dams larger in scale also signifies that it is no longer possible to ignore impacts on local residents and the environment (a “social” barrier). The coal-fired electric power plant being planned, on the other hand, cannot expect to procure any financing from donors such as the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank; this tendency is expected to become even more evident, as seen in recent trends involving the Obama administration. What might perhaps be expected here is funding by Japan for coal-fired power generation; however, actual funding is not easy to come by, as there is the risk of an off-taker breaching contract with regards to the purchase of electric power in Myanmar. Under such circumstances, the improvement of bankability (funding qualifications)9 is an issue for coal-fired power generation projects (an “economic” barrier).

Figure 3. Locations of individual power plants (excerpted from the handout of Dr. Prasert Reubroycharoen)

Barriers to hydroelectric power generation could be considered hopeless. This situation was explained while citing the Hatgyi Dam, located downstream, as an example; this case was cited by Mr. Patipat of EGAT International (EGATi), the developer of the dam. The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) and the Department of Hydropower Planning (DHPP) reached an agreement regarding the Hatgyi Dam, which was expected to have an electric power generating capacity of 1,360 MW (1,190 MW for Thailand and 170 MW for domestic consumption in Myanmar) in December 2005; an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) has already been completed for this project, but they have been unable to start construction work. The reason behind that inability to start construction is the tension between government forces and anti-government forces at the dam site. A large number of armed forces of the Karen National Union (KNU)10 has been confronting the government forces in the city of Hpa-An in the state of Kayin, where dam construction has been planned; the current situation does not allow people to approach the dam site. Security is of utmost concern in this region, and as long as tension between the parties does not relax, dam construction is not likely to proceed. For the business operators, it would be desirable to quickly gain an understanding of tensions among the locals, build trust with stakeholders, and take rapid action whenever possible.

The prospect of coal-fired power generation, on the other hand, was introduced by Mr. Nakayama of Electricity Generating Public Company Limited (EGCO), a major IPP business in Thailand. He outlined the barriers to conducting IPP projects in Myanmar, and those things that must be kept in mind when exporting power to Thailand. The preparation of an electric power purchasing agreement template, details of government compensation provided by the Ministry of Finance and Revenue, and other matters of cooperation involving the government of Myanmar were cited as issues that relate to improvements in bankability, which is the greatest single barrier to progress. Other than the above, actions cited with respect to the removal of barriers included 1) gaining an understanding of people in the local communities, by publicizing clean coal technology11 and by promoting among businesses the implementation of corporate social responsibility, 2) the preparation by government of clear environmental standards and relocation standards, and the enforcement of complete compliance, 3) the building by the government of Myanmar electricity feeder lines, and increasing the number of sites where electric power can be generated, and 4) halting the distribution of “free shares” (i.e., free acquisition of project shares) and “free power” (e.g., free distribution of electric power), neither of which is suitable for thermal electric power generation—something that bears larger running costs12 . With regards to exports to Thailand, factors cited as important considerations included: 1) whether or not the costs of coal-fired electric power generation in Myanmar are comparable to the practical costs of setting up new electric power generation in Thailand, 2) whether the memorandum of understanding (MoU) for the electric power transactions between the two countries will be “bidirectional” or “one-directional” (i.e., from Myanmar to Thailand), and 3) whether the government of Myanmar will approve a project intended to produce power for export when the supply of electric power is short within Myanmar.

In contrast to Myanmar’s difficulties with IPPs, Lao PDR has succeeded in increasing its electric power trade with Thailand, by increasing the number of large IPP hydropower projects13 . Mr. Hashimoto, Visiting Researcher at PARI, has been working for many years as a JICA long-term expert for the Laotian Ministry of Energy and Mines; he explained two sets of factors: “factors conducive to active electric power trading between Laos and Thailand” and “lessons for Myanmar’s IPPs for the future.” The facts that clear benefits can be derived through electric power trading and have been established by both Thailand and Laos were pointed out first. For example, for Laos, the export of electric power is an important source of foreign currency, and the electric power imported from Thailand can also be used to supplement the electrification of areas near the Thai border. For Thailand, trade contributes to the stabilization of Thailand’s domestic electric power supply and plays a major role particularly as a peak electric power source. The second point to be highlighted was the creation of a “win-win” situation. It is essential that thorough consideration be made with regards to Myanmar’s benefits, with respect to IPPs in Myanmar in the future.

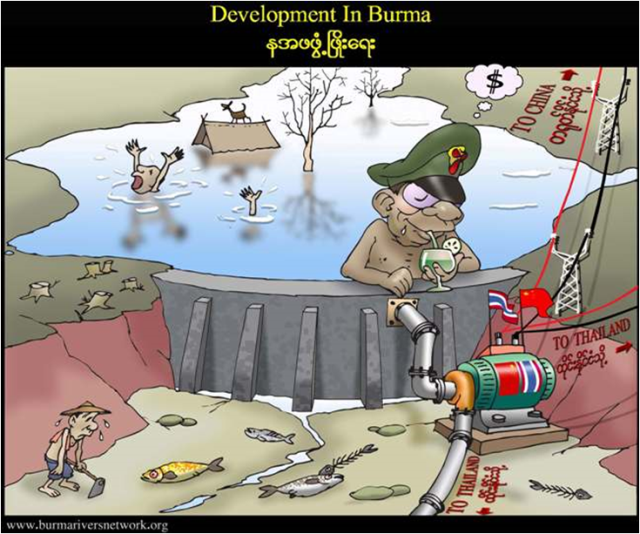

What exactly would be benefits for Myanmar? What benefits can be realized as a result of implementing IPP businesses? Mr. Yamaguchi, Visiting Researcher of ERI, introduced aspects to be considered in this regard in joint research in this term. The first is that IPPs can potentially bring about a split in Myanmar’s domestic society. For instance, even if business operators were to provide electric power at popular prices in accordance with Myanmar’s intentions, if such a benefit were to be distributed only to some stakeholders, then there will be a deepening split between those who did and did not benefit. The second point is that in many cases, the distribution of benefits is driven by existing domestic power relationships within Myanmar. In other words, it is not likely and not expected that anti-government entities or local communities would receive fair benefits; therefore, as the third point, the anti-government entities will likely harden their attitudes towards the implementation of IPP projects and become stubborn opposition forces, in union with rapidly growing civil organizations (see the figure 4). Such a mechanism can be considered one of the fundamental barriers that are common to hydro and thermal power generation in Myanmar. Carefully examining the expectations and concerns of local communities to IPP businesses and considering the means of responding to such issues may be one way of turning the tide of events onto a more productive course.

Figure 4. Image shared by some opponents to the dam

(http://burmariversnetwork.org/)

Project Professor Hisashi Yoshikawa (PARI) concluded the discussion on future possibilities, to close the session. Clarifying the perspectives of local communities is certainly an important issue; yet, in reality, accessing local communities in such a manner is considered difficult—especially when we take the case of the Hatgyi Dam as an example. The urgent matter at hand, therefore, is to build trust among informants who have deep connections to the local community. In addition, there is a need to collect information regarding trends in Chinese investments, to build cooperative relationships with Myanmar in the electric power field; this data collection would occur through EGAT and Chulalongkorn University networks. Fundamental information could then be collected to identify and eliminate barriers; this, it was emphasized, would be a desirable outcome at the current time.

Footnotes

- IEA - The Energy Development Index

- An IPP is an electric power generating business conducted inside Myanmar, for the purpose of distributing power to power companies in Thailand.

- his has been conducted periodically since September 2013, with the intention of providing specialized education and personnel training for government officials involved with Myanmar’s energy policies. See: /event/act140901.html (in Japanese).

- This is based on the assumption that electric power can be supplied from the power grid to areas within a 40-km radius of a substation.

- We classified rural communities in terms of whether or not hydroelectric generation may be possible. This was based on the particular assumption that electric power can be supplied through hydroelectric power generation to about 10% of the country’s rural communities.

- The calculations were tentative and were insufficient for use as the bases of negotiations in JICA, Asian Development Bank, and World Bank projects.

- This is a reference to the presentation made by Professor Sakata, the Director of PARI, at the beginning of the morning session.

- Furthermore, the construction of more than 10 gigantic dams is said to be planned upstream of the Salween River in the Yunnan Province of China, where the river is called “Nu Jiang” (“angry river”).

- A state in which banks are able to offer financing is referred to as a “bankable” state. At a bank hearing, it has been said that for Myanmar IPP to become “bankable,” the “Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand needs to purchase 100% of [its] electric power” from it.

- This is an armed organization of Karen (an ethnic minority in Myanmar) that aims to extend its autonomous rule. A variety of factions are popping up at the present time.

- These are technologies that constrain environmental burden by using coal efficiently. Such highly efficient electric power generating technologies include supercritical pressure and ultra-supercritical pressure, inter alia.

- For existing hydroelectric power generation for export to China, it is said that 10% of shares and power are earmarked as “free.”

- Laos aims to become the “battery of ASEAN” by increasing its numbers of IPP hydroelectric power generators and exporters. A representative project related to this aim is the hydroelectric power generation plant at NamTheun 2.

Related Links

The 2nd PARI-ERI Joint Workshop Detailed Report - ASEAN Connectivity: Power Integration between Thailand and Myanmar

The 2nd PARI-ERI Joint Workshop Flash Report - ASEAN Connectivity: Power Integration between Thailand and Myanmar

The 1st PARI-ERI Joint Workshop Report - The Evolving Energy Relationship between Thailand and Myanmar - A View From Thailand -

Global Energy Policy and East Asia Research Unit

Energy Research Institute, Chulalongkorn University